Sherri was from Florida and smoked Marlboro Lights, the kind of girl who could make that seem like a personality trait. She was from a small podunk town—an impoverished coastal shithole so oppressively humid that the default uniform consisted of tube tops and short shorts that barely concealed the beads of sweat slowly tracing down her tanned, hairless legs.

Her world? It was one long, fever-dream of a place: double-wide trailers, crack cocaine, neon-lit titty bars, hackneyed tattoos that looked like someone had gone at her skin with a pocket knife and a bottle of tequila. There was no cool factor, no edgy irony. It was just survival—bare-knuckle, no-frills living. Her motto? “I need my shit.” And that was it. That’s what you got.

I liked Sherri a lot. Maybe it was because I understood her vibe more than I wanted to admit, or maybe it was because she made chaos look kind of glamorous. So when she asked me to house-sit her Palm Springs place for the weekend, I said yes. Sure, I told myself it was because I wanted to lounge by the pool, but really? It was the neighbor. The ex-game show host who’d gone off the deep end, who thought climate change was a hoax and spent his days drowning in vodka. I wanted to go hang out with him and talk about how the world was unraveling and experience second-hand fame by proxy.

“You can smoke pot inside,” Sherri said as she tossed me her house key. “But there’s no internet, so good luck staying sane.” She paused for effect. “And keep it mellow. No Miles Davis crap.” The reference went over my head, but I didn’t ask. With Sherri, not knowing something was just another way she made you feel stupid.

The house was a time capsule from the Nixon era, complete with shag carpet that smelled faintly of mildew and a TV that looked like it could double as a bomb shelter. There was no way I was going to be productive here, so I surrendered to the retro vibe and found myself watching an old episode of Bewitched from 1969. L.A. Rams receiver Jack Snow guest-starred, inexplicably zapped from a football field to a department store—improbably rerouted from the gridiron to sitcom purgatory. He spent most of the episode looking dazed, mumbling, “I was just playing the Cowboys in Dallas, Texas.”

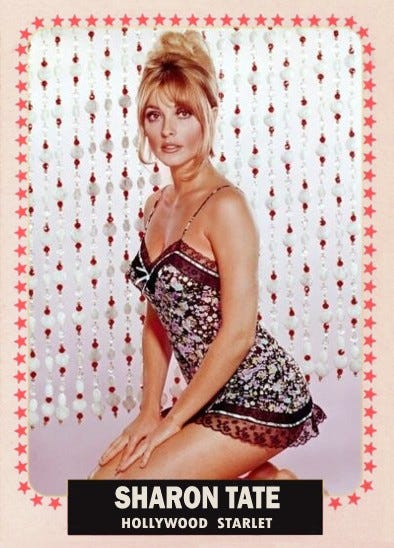

Then came a chilling Rosemary’s Baby reference, which jolted me out of my haze of kitchy escapism. This episode aired just six months before Sharon Tate’s murder, the event that obliterated the “Summer of Love” with brutal finality. The Manson murders—triggered by a bizarre, unrelated grudge involving nepo-baby and Byrds producer Terry Melcher—loomed over this otherwise breezy sitcom like a dark cloud. Even Dennis Wilson of the Beach Boys, who had accidentally paved the way for Manson, was tangled in this mess of fame, violence, and bad choices. His attempt at a solo music career? Forgettable. His willingness to fuck feral, mud-smeared hippies with gonorhea? Legendary.

Sitting there on that sagging, cigarette-burned couch, I realized this wasn’t nostalgia; it was a cruel time machine, a grim carousel spinning through the fabric of decades gone by. Everything was connected by this thread of absurdity and despair. A masterpiece, if you were willing to squint. Sherri, her canceled neighbor, Jack Snow, Sharon Tate, Manson—all of it felt like one long, twisted mess of absurdity. Because, in the end, it was all the same story: time eats everything, and we’re all just waiting for it to finish its meal.

I get excited every time your work shows up in my email box, I say the same compliment, well done!

Your stuff is always good, man, but I think this one is really excellent. Ya know, for whatever my opinion is worth.